clearing the decks: yes the tech enthusiast side of the "AI" debate is bad, we know

We already know, and it is a waste of air to keep pointing out, that everything coming out of the mouths of the venture capital freaks of the silicon valley and the linkedin influencers is a nightmarish sludge of inane nonsense. It's a mix of blind tech enthusiasm (this tech will provide unlimited power to all), libertarian fantasies of not having to interact with the economy (cutting out the middlemen... or the workers), and naive hope that this tech will make artists' work easier and not increase the rate of exploitation (in defiance of every historical example in existence).

In 1851 mechanical sewing machines became commercially available devices. They were widely advertised as household appliances that would free women from the chores and drudgery of hand sewing. Whether women sewed at home for their own use or were seamstresses working for others, the promise was liberation from toil. Not only were individual women to benefit from the devices, but there were high hopes for humanity as a whole. [...] But what actually happened of course was not like this at all. Though machines were indeed used in households and became part of home furnishing, the major development was a use in the factory setting. The resulting sweatshops exploited the labor of women and particularly of immigrant women. Sewing machines became in fact synonymous not with liberation, but with exploitation.

Ursula M. Franklin, Real World of Technology lectures (part 4, ~21m)

We also know these people talk like this because they need the hype cycle to fund their ventures. When Karl Marx talks of capital as a force that possesses people like a demon, this is what comes to my mind; as far as i am concerned there is no point talking to these people as if they were human, not until we know how to remove the parasite of capital from the drivers' seat of their brains.

There are a lot of legitimate criticisms to be made of specific ways "AI" and machine learning are deployed. If anything, the application of this stuff to art generators is the least damaging - compared to its half-assed application in medical fields, as replacement of social systems of support, deepfake porn, unprompted phrenology wet dreams, not to mention its use by law enforcement to wash their hands off racial profiling, and of course the nexus at the center of all technology development under imperialism: the military-industrial complex.

There is a wide breadth of criticism to read on these issues, spanning from more than a decade at this point; the scope of the topic is way beyond a measly blog post. I will not get into these criticisms, because they have not been part of the discourse cycle that i want to address. Rather, i want to zoom in on the discourse heralded by the release of OpenAI's DALL-E and Midjourney to the broader public, which focuses exclusively on the role of AI image generators and how artists should "protect themselves" from its effects.

I will also not address pontifications on either side of the debate about the nature of human consciousness / creativity / intelligence, which do not have any bearing on whether this technology get developed or how it is applied to our lives.

I want to debunk criticisms that have dominated the discourse among professional artists (particularly among illustrators, concept artists, and other folks whose pieces are most directly comparable to AI art generators' output), and their attempts to do counter-activism. The process will reveal more of the petty bourgeois brainworms that plague the arts milieux; and if there's anything i love rapping about on this blog, it's this. So let's get going.

the artist reaction: reactionary!

Among the loose social crowd of online artists and creative hustlers, the reaction to this new technology has been short-sighted at best. While there are legitimate grounds to criticize the way this technology fits into systems of exploitation, the arguments from the self-identified artists tend to follow a few distinct lines of thinking:

- the ontological difference of human creativity / the artist's superior mind (the mild version of this take compares it to "the stupid machine", the explicitly exceptionalist and dehumanizing version compares it to other, less intelligent/imaginative humans and lazy parasites)

- An ideology of arts that posits artists as uniquely more human than the masses; or that posits "creativity" as a universal right but doesn't stop to ask why only some people are allowed to make it their life's purpose, as opposed to a hobby they have limited time for.

- the unalienable right for the artist to hold onto their creative output as private property, to be protected from "theft" (which in the case of AI art becomes even prospective theft, like an extension of protections against plagiarism shifting into an unconditional protection against replacement by other artists with more productive tools)

- An ideology of arts that relies on the frameworks of private property and copyright, without a clear understanding of how these frameworks came to be and how much of a danger they are to both individual artists themselves and culture at large.

- the displacement by more efficient AI methods of the artists' conditions of economic existence; the erosion of their market share, client pool, contract opportunities, etc. This argument is legitimate, but answers to it tend to fall back into the above reactionary pitfalls that will eventually turn against the artists that promote them, as we'll get into.

These criticisms focus entirely on the effect of the AI image generators on artists and don't really understand how they work, which is why they focus on the AI models' output and gathering of images and not on the more seedy aspects of the whole deal, which concern the labelling of the massive amounts of data they require.

We live in a culture saturated with images. For the longest part, the classifying part was the hardest, assembling the pair. That's because it was done by hand, by people paid or incentivized to do it (or who were somewhat aware of what they were doing, like when we solve a Google Captcha). What was innovative about Dall-E 2, and then opened the floodgates when the other labs realized they could do the same, is using publicly available data from the web. The image descriptions done for SEO and accessibility reasons stored in the alt fields are a treasure trove of readily classified data, for example. These descriptions are sometimes written by the artists, but for the amount of data needed, it's almost certain that they've used images described by critics, curators (from museum websites, for example) and especially by anonymous data entry and SEO people (on stock image sites) or by random internet users assembling image boards on Pinterest, blogs and the likes.

never workers: the denial at the heart of the Artist ideology

The artist is therefore neither bourgeois nor proletarian: they exist in a pre-capitalist economic relation, as artisans. Rather than diminishing the ideological dominance of the capitalist class over the Arts, this strengthens it. It does so for two simple reasons:

· if one does not garner a wage from their labor, they must already be in possession of wealth;

· the sale of artworks on the market is the only manner in which their character as social products may be realized; that is, it is the only way in which they may be realized as art.

Prolekult, A Dying Culture Part four: Art and Capital

The artist condition, at least for the crowd of creative hustlers and entrepreneurs that has been most vocal on social media, is one of artisanal production in an increasingly incompatible economic system. As creative fields get absorbed into the broader capitalist economy, the conditions of existence of craftspersons and artisans are clawed away, yielding to the conditions that govern all capitalist industries: the separation of means of production and labour into distinct classes, industrialization and the division of labour into specialized disciplines, etc. This is already the state of affairs for the vast majority of creative fields - film, animation, videogames, a significant chunk of the literature industries, etc.

However, the ideological framework that is still relied upon to understand the arts remains attached to this idea of the artist as a lone artisan, working on pieces on their own (or in small groups), with control over the means of production (tools and materials) and the output (with the understanding that they need to satisfy clients' needs - but they are not under orders from a manager).

This ideology of arts collapses different modes of artmaking and culture:

- it collapses culture as a social relation between people and groups of people, and art as a career track; and deploys criticism of AI art and other new developments in the field from the standpoint of the latter

- and within this reduction of art to a career track, it collapses wage labourers (workers) in "creative industries" and artisans / entrepreneurial (petty bourgeois) artists; and deploys criticism from the standpoint of the latter.

Wage workers produce their work for an employer (or studio/company) in exchange for pay - the pay is based on their labour, and not on the revenue of the end product. Artisans and the bourgeois, on the opposite end, make money by selling products to customers on the market; the money they make is tied to that revenue.

There are a few niches of artists (speaking here of people who make their money as artists, to whom art is work) who essentially constantly shift between the two standpoints: for example freelancers who work for big clients that are in practice their employers, while simultaneously selling commissions and niche art products to customers.

Crucially, the mainstream ideology of artmaking and art-working reduces all interests and aspirations of the art milieu to those of the artisans and entrepreneurs. Even artists who alternate between both positions are encouraged to think of their true goal and position as the petty bourgeois one while thinking of the contracts they do for big employers as a temporary embarrassment - selling out because you need to, and only until the meritocracy recognizes your hard work and pulls you back into the ranks of the small bourgeoisie. As for hobbyists who rely on other work for subsistence and do not sell their art or skills on the market, they are bombarded with calls to make their art into a hustle, which is presented as becoming a "real" artist as opposed to a mere amateur.

There are legitimate reasons why being a wage worker is less appealing to artists than being an artisan or entrepreneur: it involves alienation from your own labour, which you lose control over; and that has an especially heavy weight in these fields where much is made of the pristine Soul and Ideas of the artist. But it is important to resist the narrative that there is an ontological difference here between the alienation of an artist who has to draw assets for a random corporation's marketing campaign, and the alienation of a manual labourer who has to participate in the daily operation of a manufacturing plant that they have no control over. Alienation is alienation, and artists do not deserve an exceptional waiver from alienation compared to other types of labour - or rather, all people deserve freedom from alienation; but as long as some are alienated, we have no right to claim a privilege that they are denied. A liberation that comes at the price of our complicity is no freedom at all, it is a bribe.

meritocracy, martyrdom & mystification

By collapsing entrepreneurial artists and wage labourers, and identifying all interests with those of pettybouj entrepreneurs, the way we understand ourselves as artists reinforces the inequality of the field. It obfuscates the unfair privilege that successful artists benefit from, and pushes the less-successful ones to reactionary martyrdom and endless sacrifice instead of seeking working class structures and solidarity. Rather than building bridges between working artists and workers in other fields, poor artists are encouraged to hustle and grind against competition from moneyed corporations and celebrities, while berating their audience for not making the right consumer choices if that doesn't work out. While the idea that society and the economy operates (or should operate) on a meritocratic basis has been thoroughly debunked, it remains deeply entrenched in the attitudes of artists.

There is also a generalized refusal to acknowledge the contradiction between art being either work or an avenue of individual self-fulfillment. This tension is no news to any artist, but rather than confronting it for what it is (and confronting their personal guilt), some prefer endless performative hand-wringing. Others retreat to an entirely entrepreneurial position, to the tune of "if you work doing what you love, you won't be working a single day".

Before AI art became this fearsome challenge to the artists' identity, it was a mainstream point of argument among artists that doing art was skilled work. Against the idea that artists were just "born with it", many took much pain to explain that all art forms involve a lot of specialized training, that you get good at drawing not through natural luck but through hard work. This reaction responded to an anxiety about being seen as a legitimate field of industry, to be on an equal basis as specialized workers such as engineers, doctors, etc. - and deserve the same compensation.

Since AI art came in to displace artists, the tune has suddenly completely reversed. Art is now an inherent capacity of the soul, and anyone can do it. Why use these AI image generators when "anyone can pick up a pencil and draw"? Doesn't even a bad drawing "have more Soul and Meaning" than a result generated from the recombination of other art pieces? Suddenly the notion of arts as a skill with technical components flies out of the window.

Both attitudes reflect anxieties about seeing your work respected as such, while also refusing the industrial implications of art being a form of work, and subject to the same market forces as all other fields. This is an attempt to have your cake and eat it too that resonates with my earlier critiques of idealism among indie game developers.

Apologies to this mutual but this is a Bad Take

These arguments often reveal an incredible disdain for most people, in line with the exceptionalist thinking that plagues the arts milieux.

The argument that "anyone can pick a pen and draw" is simply condescending. A shitty pencil drawing photographed with no post-processing might have "soul" to some, but does it fit as an asset into a game/film/etc project? That tools like AI art generators can be used as part of a broader production pipeline is completely overlooked, while the people who use them are assumed to be simpletons who simply want an image to look at, and have no plans beyond it. Hobbyists already make regular use of stock images and photographs in games, in zines, in film projects; and it isn't hard to imagine how art generators can fit in this process - they already do!

the great serpent at the heart of the AI arts debate: intellectual property

Reliance on a producer-owner framework and individual property is leading artists to develop the tools that are eventually used to abuse them. The slightly batshit campaign to "support human artists" posits that the best way for artists to fight back is to pay a lawyer and lobbyists to beg the government for harsher IP laws, by teaming up with the Copyright Alliance - an organization whose members include representatives from Disney, Netflix, Getty, Adobe, Sony, WB, Nike... You name it.

IP has, from its very inception, been wielded against small artists and culture writ large - whether we're looking at artists being DMCA'd or sued by corporations for fanart, being muzzled by endless NDAs and stuck in a limbo where they can't show their work, or more generally attempts at destroying public culture (which includes private corporations limiting the release of works from deceased artists, taking it away from the public). If that sounds dramatic, just look at the ongoing attempt by publishers to destroy the Internet Archive and take libraries out along with it, kicked into gear by Chuck Wendig in the name of "young authors, debut authors, and marginalized authors who are already fighting for a seat at the table". Meanwhile, corporations and celebrities alike constantly steal from smaller artists, knowing very well that there is no way for them to fight back against their comparatively infinite means to bleed them dry at the courts no matter the verdict.

There are contexts where artists can wield IP to protect themselves against the appropriation of their work by employers or distribution platforms, for example by keeping the rights to their work and licensing it to the employer for specific uses instead of yielding the rights wholesale like in a standard "work for hire" agreement. But by teaming up with corporate monopolies like Disney, the campaign to support human artists is putting the gun in its executioner's hands. IP is an unreliable weapon, and the only way we'll be able to use it for our benefit as working artists is by backing it with worker power, not corporate power - with the understanding that it can easily turn against us and that stronger IP legislation is not a good in itself. The spaces where these strategies can be teased out aren't monopoly-led lobby groups or the US courts, they're unions: they are already the means through which contracting standards can be established where artists get to keep the rights to their work instead of giving it all up to the employer, and clauses around the use of AI by employers could be developed along the same lines.

The fact that most of the posts about "art theft by AI" focus on superstar artists with a big name and brand is no accident. The common denominator between all of these drives to reinforce IP is that they come from already successful artists trying to secure their position, using the language of protecting the underdog for their own short term benefit.

This is exactly in line with last year's push to adopt NFTs, which also dangled intellectual property as a lure to make anxious artists embrace the technology. Of course, this changes absolutely nothing of the existing power balance of the economy, and poorer artists were immediately taken advantage of - if anything, more art theft happened thanks to the NFT craze opening the door to grifters of various stripes. Topically, one of the main figures attached to the campaign to support human artists happens to be an NFT evangelist.

But if people try and try, at some point a campaign will succeed, especially if it's coopted by a larger entity that better understands the tech and the nefarious possibilities opened by the "reforms" needed to address these artists' concerns. Think only about the way Hachette Book Group, HarperCollins Publishers, John Wiley & Sons, and Penguin Random House used Chuck Wendig to sue The Internet Archive, with effects that will surely create precedents affecting other non-profits and the library system.

You don't have to think very hard to image some sort of new DRM dictating how images are shared and described online. Let's even invoke a nightmare scenario and bring the blockchain into discussion. Both smart contracts and NFTs could "solve" the problem, in all sorts of ways that I don't want to think too much about because I'll get sick. But some quick examples, just to show I'm not full of shit and paranoid, would be minting a number of NFTs to an artist proportionally to how often their name is used in a prompt; or smart contracts transferring to the original artist a fraction of the money involved in each transaction where an image strongly influenced by them is involved.

I hope it's obvious how such an arrangement would be detrimental to most artists. First of all, as we've established, in order to get the model to do a compelling Kim Jung Gi, it'd need the input of a lot of other people who aren't Kim Jung Gi. His name would absorb the value created by all of them like a sponge. And there's nothing to say that such an arrangement would be relegated only to ML generated art. If all this architecture is put into place, it'd be trivial to implement systems to prohibit saying you're inspired by Ortiz, since her name attracts clients and gets better SEO, unless you've got the token received after following her workshop. This is a recipe for cartelization and monopolization.

the spectre of proletarianization

Proletarianization is originally the marxist term referring to the process through which pre-capitalist producer-owners get turned into proletarian workers through the systematic theft of their means of production by the nascent bourgeois class, as it established the capitalist mode of production as the new norm. This is now a process that also applies to the petty-bourgeois and the artisans when capitalist industry outcompetes them, and forces them out of the owning class - turns them into wage workers. It is the process of being alienated and dispossessed of the control you have over production - which means dispossession from means of production, which means dispossession from... everything but your ability to toil. It sucks! But for artisans and the petty bourgeois alike, resisting proletarianization is often articulated as maintaining their current status in the oppressor camp against the already proletarianized.

The lower middle class, the small manufacturer, the shopkeeper, the artisan, the peasant, all these fight against the bourgeoisie, to save from extinction their existence as fractions of the middle class. They are therefore not revolutionary, but conservative. Nay more, they are reactionary, for they try to roll back the wheel of history. If by chance, they are revolutionary, they are only so in view of their impending transfer into the proletariat; they thus defend not their present, but their future interests, they desert their own standpoint to place themselves at that of the proletariat.

Karl Marx & Frederick Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party

The process we are outlining here is much bigger and older than AI art, though. It is tempting to frame the role of AI art and machine learning models as one of primitive accumulation or enclosure of "commons": they take the art that had been published in a freely accessible manner online, and turn it into a resource for the generation of new images - crucially, in a black box that belongs to the corporations that own the machine learning software and the trained model itself.

Except this isn't really the full picture. It's a convenient narrative for artists who want to frame themselves as an anticapitalist communalist community being sucked dry by the evils of industry, but the analogy falls apart under scrutiny - the images that were posted online can be reproduced infinitely, and no "theft" or privatization in the classical sense occurs in this process, so it cannot be seen as enclosure; besides, the ways these models are trained is misunderstood by most of the mainstream discourse around them, which makes no distinction between the training process for a model and its later deployment, after it has been trained and the training data cannot be reverse-engineered. The obscurity of machine learning models, and the lack of tools to "navigate" and interact with latent space, do work in the benefit of the private corporate entities that own these models; but that is a distinct issue from any straightforward transfer of capital from artists.

This is an important distinction to make: this technology is part of a broader pattern, which is the universal pattern of capitalist development of industry. It is one among a myriad of advances and tools that are developed for the specific purpose of increasing the efficiency of production, without any concern for morals or consequences, only the forces of competition and profit. AI technology might (will) accelerate some existing tendencies, but it is not the root of the issues facing workers, and this misattribution is a double mistake: it removes the positive potential of these technologies from the picture, and it takes our attention away from the causes of the problem, making us powerless to fight it.

A key element of the development of capitalism is that industry develops and work becomes socialized - turning from individual or family-based commodity production to the large scale production of commodities that can't easily be attributed to the hands of a single producer, or a discrete group of producers; where instead a large mass of workers operate a sprawling production process (whether a factory or any kind of "digital production chain") that spouts a mass of commodities in which the individual touch of producers becomes indistinguishable and impossible to attribute. But it's important to make the distinction between socialization and dispossession - just because the scale of work means individuals can't own the entire production process any longer, doesn't mean that democratic structures can't be built to oversee it collectively, and maintain collective ownership of the process - just like the factories had to be built to sustain the shift from individual handicraft to large scale semi automated production, social structures can be built to administer them as a group.

socialized labour VS private property

The AI debate is the latest in a sequence of symptoms that emerge as a result of a common economic phenomenon: the inherent contradictions of the capitalist mode of production. Its class system (which forces the separation of producers into an owning class and a working class) works alongside the rising scale of production, the increasing productivity of industry and the intensification of competition; and constantly pushes whichever handicraft and artisanal production niches exist into the past as industry takes over the field.

Artistic fields and branches of "creative industries" are at various stages of that process, some more industrialized than others. But the capitalist system is now the world's dominant mode of production, and all arts fields are enmeshed in economic markets and production chains. The work of digital artists, before AI enters the picture, is already socialized and part of a global production chain of computer tech, digital media, global communication platforms, etc.

The socialization of arts isn't the problem. But when socialized production is combined with private ownership, it means dispossession for people who until now operated as artisans, individual producer-owners. As a result, artists tend to respond to these changes with a response that betrays the individualist artisan position that they refuse to let go of. But fighting socialization with individualism is a losing game, and deeply reactionary - it is the same reaction that makes the middle class, entrepreneurs and small business owners the social base for fascism.

I truly believe that this superficial reaction, whereby we attribute these issues to the scale of industry itself and fetishize small scale production, is a major stumbling block even among the left. We find it everywhere in discussions of industry and technology, sometimes couched in cottagecore primitivist fantasy, other times in very questionable comments about industry in the USSR, in China or in the 3rd world generally speaking - Ursula Franklin's Real World of Technology lectures, which were quoted earlier in this blog, are one such example: while she explains several times that technology is a social relation and takes a shape that responds to power relations (therefore capitalist class relations in contemporary times), her framework of holistic VS prescriptive technology still eventually loops back to this particular dead end - locating the difference between the two in the scale of production, and not in the alienation of wage workers through private ownership and control of the capitalists.

The individualist fetish is present everywhere as a result of the hegemony of liberal ideology - we are trained to see ourselves as entrepreneurs, and to assume that any collectivization of the production process is synonymous with the loss of our individual freedoms. We miss the forest for the trees. The answer to the contradiction between socialized production and individual property isn't to reprivatize production, but to socialize property.

Sidenote: decommodification!!!

The art and culture that still operates outside of the market or on its margins already gives us a glimpse of what socialized art production could look like, art made by the people and for the people, rather than to increase the rent revenue of a monopoly's IP franchise.

What does decommodified culture look like? Consider mods, fanfic, etc. - works that are themselves derivative, yet don't threaten the original work and exist in conversation with it. They are example of art made within a collective social fabric, with its own stakes surrounding copy and reuse, but free from arbitrary market frameworks such as IP (if not actively wrestling them).

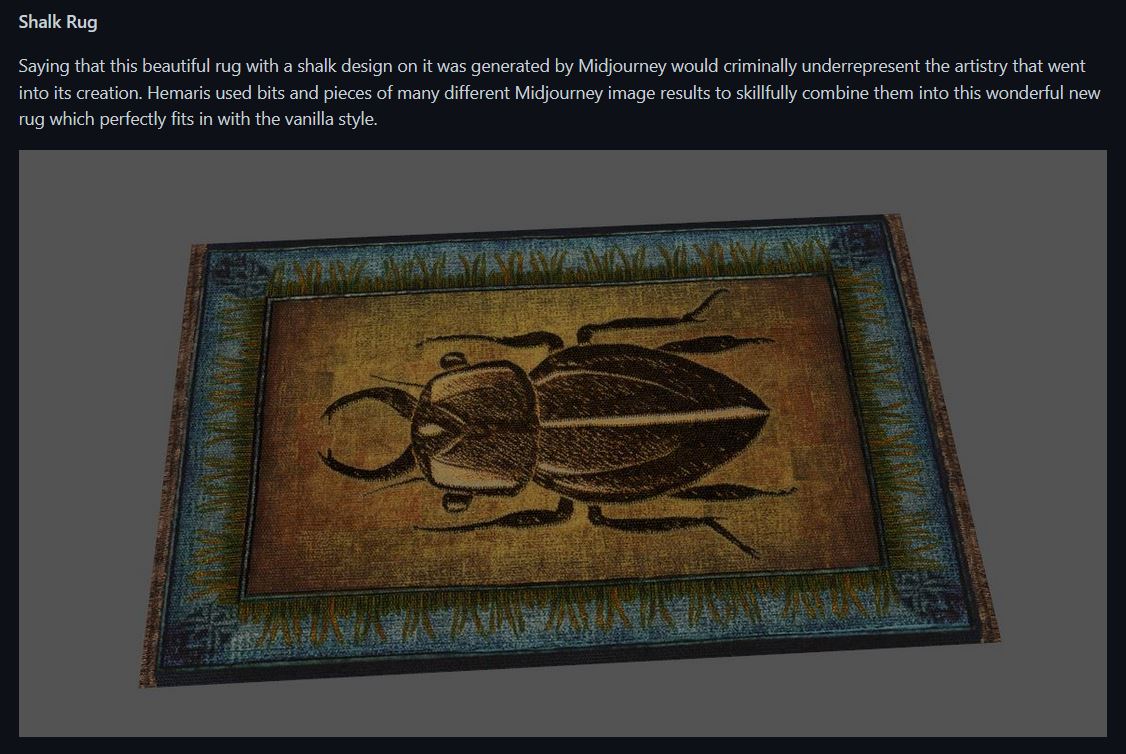

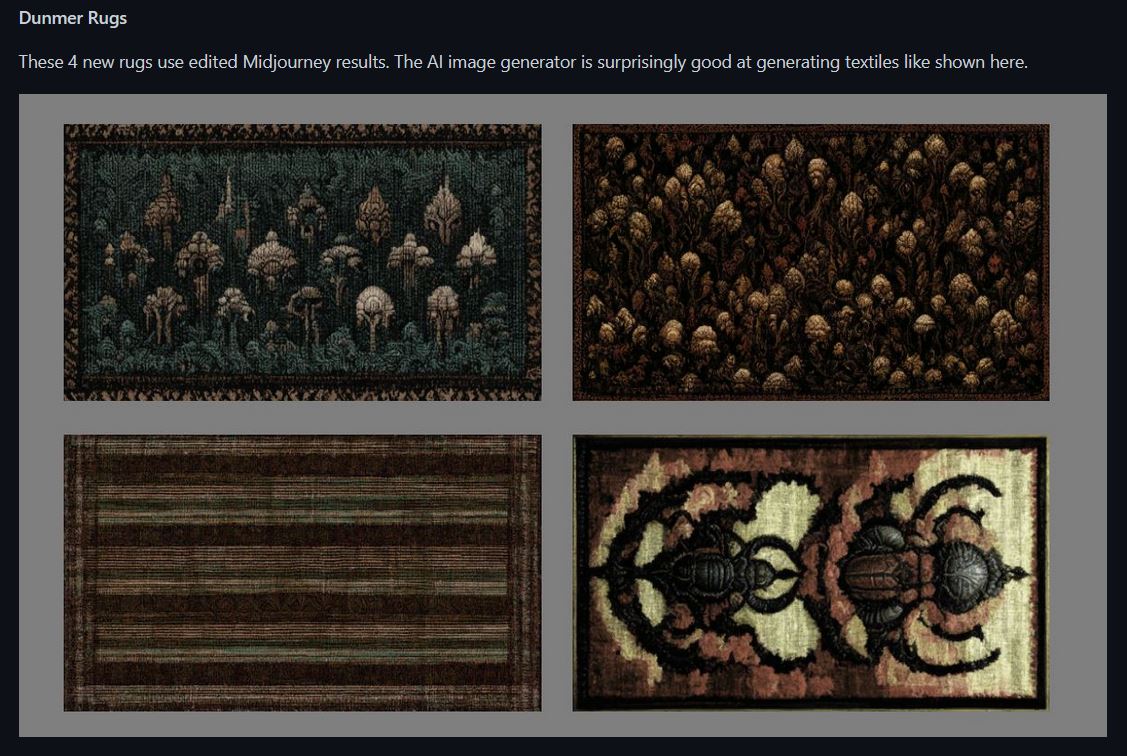

We can already find some great examples of the use of AI image generators as part of bigger projects in the modding community

Release 2.0.0 of the OAAB_Data asset repository for the Morrowind modding Community

It is no coincidence that work by hobbyists and students is often the most interesting: they are works made outside of market incentives, or at least in contexts where it doesn't have the same weight. We can fight for a future where artists - no, people of all stripes! - get to experience this freedom throughout their lives rather than just for a few years (and that's provided their free time isn't entirely consumed by working side jobs to afford the luxury of education to begin with).

We already make our stuff public when we post it online, and we do it to share it with peers and strangers - it turns an individual indulgence into a social relation, and turns the artifact into a piece of culture. Confronted with the implication that this piece can then be used by others - to copy, to remix, or to feed to an AI training pool - some react with reflexive greed, and lock their pieces away from public eyes. This is the most depressing thing i can imagine, the equivalent of art barons purchasing pieces only to lock them away in a windowless safe in their mansion's basement, only the artist themself is the one doing it. We must not lock culture behind intellectual property; we must fight for a world where your work being copied doesn't rob you of your income, where it just doesn't matter that much.

Apologies to this other mutual but this is also a Bad Take

Culture is constantly fighting against the commodity form and private property. All major movements in visual arts, music, writing, have their origins outside of any kind of market.

the worker struggle for technology

Ironically, the tech enthusiasts and the artist reaction to AI are 2 faces of the same coin. The application of the tech will have its biggest impact in industrial production and has its most positive potential outside of the market entirely, but all we hear focuses on individual producer-owners and small business. The musings on either side of the discourse have no bearing on the economic forces that are determining the actual outcome of this fight, and offer no clarity whatsoever, only pipe dreams and catastrophizing paranoia. We are looking at the deployment of a new technology in an industrial field, and nothing about that process is new: the starry-eyed promise of the technology's potential will make way for very mundane applications as it is applied in existing production processes, the increase in productivity will be matched with a devaluation of workers' labour and increased exploitation, small enterprise will be outpaced by industrial competition, and wealth will concentrate in the hands of the big fish while the vast majority of the masses finds itself more alienated than ever.

The labor of digital creatives and innovators, sutured as it is to a technical apparatus fashioned from dead labor and meant for producing commodities for profit, is therefore already socialized. While some of this socialization is apparent in peer production, much of it is mystified through the real abstraction of commodity fetishism, which masks socialization under wage relations and contracts. Rather than further rely on these contracts to better benefit digital artisans, a Marxist politics of digital culture would begin from the fact of socialization, and as Radhika Desai (2011) argues, take seriously Marx’s call for “a general organization of labour in society” via political organizations such as unions and labor parties. Creative workers could align with others in the production chain as a class of laborers rather than as an assortment of individual producers, and form the kinds of organizations, such as unions, that have been the vehicles of class politics, with the aim of controlling society’s means of production, not simply one’s “own” tools or products. These would be bonds of solidarity, not bonds of market transactions. Then the apparatus of digital cultural production might be controlled democratically, rather than by the despotism of markets and private profit.

Gavin Mueller, Digital Proudhonism

So what do we do? We acknowledge that this is one of the many facets of the class war between owners and toilers, and that power will only come from mass organization of workers. Fight along labour struggles, get involved in working class organizations.

The Luddites, who have been a point of reference on either side of the AI discourse, are actually a better example of this than they are often made to be:

Between 1811 and 1812, hundreds of new frameworks were destroyed in dozens of coordinated, clandestine attacks under the aegis of a mythical leader called “Ned Ludd.” In addition to their notorious raids, the so-called Luddites launched vociferous public protests, sparked chaotic riots, and continually stole from mills—activities all marked by an astonishing level of organized militancy. Their politics not only took the form of violent activity but was also enunciated through voluminous decentralized letter-writing campaigns, which petitioned—and sometimes threatened—local industrialists and government bureaucrats, pressing for reforms such as higher minimum wages, cessation of child labor, and standards of quality for cloth goods. The Luddites’ political activities earned them the sympathies of their communities, whose widespread support protected the identities of militants from the authorities. At the height of their activity in Nottingham, from November 1811 to February 1812, disciplined bands of masked Luddites attacked and destroyed frames almost every night. Mill owners were terrified. Wages rose.

Gavin Mueller, Breaking Things at Work

Notice that the demands of the Luddites emphasized the class relationship at work: they were fighting for wages and working conditions, not merely for quality standards for the end products or professional gatekeeping.

Similarly, recent union struggles over automation have not called for the total abandon of new technologies; rather for employment guarantees, training for the new tools and methods deployed, and a say in their implementation.

Does this mean the tactics of the luddites can be applied wholecloth to our AI conundrum? Not so much: the terrain is very different. Our current landscape, where hobbyists find uses for the technology outside of the market, and where AI models themselves sit awkwardly between open source public access and total privatization, calls for its own response. And are we supposed to destroy our personal computers, hack github repositories, or commit arson at the data center? Maybe the campaign to ruin the artstation homepage with anti-AI messaging can be interpreted through the lineage of luddite sabotage (if you squint); the campaign to tighten IP and copyright in response certainly cannot.

What we know for sure is the following: we like the luddites will only find meaningful power in mass organization as workers, against those who try to maintain full control over the technology, and its deployment into our lives. How we approach the different facets of this fight - control over technologies and production methods, working conditions, the preservation of wage standards in the face of increased productivity - will depend on the specifics of each industry or workplace. And this fight will happen on all ends of the technological development process: with workers whose job will be "automated" by AI, workers who will fill developing "AI handler" roles (labelling training data, curating outputs, operating new AI tools in production chains), and workers who develop AI technologies to begin with. In fact, the latter already have a headstart.

Either way, it is a fight that can only be fought and led by workers in industry, not small artisans scrambling to save their economic exception.

Understand the power struggle and pick a side. Doing this involves some real soul searching for artists, who were either enjoying the special status of the petty bourgeoisie, or aspiring to them. That's the price to pay for the privilege we've had thus far, or the ticket to freedom from endless sacrifice for a dream of success that'll never happen.

Footnote: fighting the real AI - the market

This guy is famous he doesn't get to be anonymized

Except that's actually not an unfair opinion to have about mainstream commercial art, is it? The imagery coming out of the "marvel-netflix-disney-epic media industrial complex", or however we want to call mass media industries, is arguably absolute formulaic dogshit on the whole, and pushes grab-bag IP exploitation to almost absurd ends. And for all the fuss about AI ruining Artstation, that platform's homepage was already known to inevitably select for an indeterminate sludge of derivative high fantasy concept art pieces and big titty elf 3D sculpts.

(Note Artstation's staff deflecting the blame to "fans" with the usual derogatory and exceptionalist artist verbiage we've decried earlier. normies just don't know what's good!)

For all intents and purposes, art produced for the market is already procedurally generated by market forces. The process of selection is at play at both the inception end (by selecting which projects get funding, and even prior, which creators and modes of production are allowed to thrive in the industry) and at the distribution end (through competition between pieces - which is a matter of marketing and platform penetration much more than any kind of metric of artistic merit, if such a thing really existed in the abstract). Can the capitalist market not be described as an analog algorithm optimized for the maximum production of abstract capitalist profit without concern for any other metric?

Now that's the kind of rogue AI i want to tear apart.

2 years later: complimentary AI art takes

July 2025

It has been more than two years since this post was originally published, and AI is still a hot discourse topic on a weekly basis.

Here are some extra notes on the matter that i find important to add in hindsight, and in response to some reactions to this piece.

:::

On the question of how to address or combat the views that i criticized in this article (this is the most crucial addendum):

Part of AI art opposition is petty bourgeois self-interest from some artists, but part is also just a natural and legitimate reaction to alienation from people who might struggle to articulate it or even understand it. When someone says "AI art has no soul", there is a fascist version (artists' skillset makes them übermensch) and there is an alienation response (i expect art to connect me to other people, but this is like an Ad / marvel slop) - and i think it is Our Task as marxists to elucidate this distinction. Because the second read here is naive, but it can be pointed at something real. It can be productive!

The question then is whether we are talking to someone who is/will be on our side but needs mystification undone, or to a forever class enemy we can tear into. We have to read some Mao and get serious about treating contradictions among the people differently from contradictions with the enemy. The concept of "artist" obfuscates this boundary so this requires rigour!

Screaming "you petty bourgeois fascistoid artisan" at ultimately harmless randos online who don't know what that means, on the other hand, sounds to me like a waste of time for everyone involved.

:::

What we currently call AI does not "democratize" anything. Some proponents of AI art have been defending this idea from an allegedly marxist standpoint, i believe that is completely wrong and opportunistic. As long as so-called AI tools operate in the world of private property and the market, art made with them remains commodified - and even if free AI tools emerge, the same applies if they are used in industrial production processes. Democratizing art only happens through increased leisure time!

:::

Productive tech by itself is not liberatory. Under capitalism, increases in production to not translate to better lives for the working class; on the contrary, they are a tool for the owning class to increase the rate of exploitation. It is true that 1- under capitalism the coming-together of the working class in socialized production processes is the precondition to the development of a truly collective, altruistic, revolutionary consciousness; and 2- under communism, advances in production will allow for greater emancipation and higher living standards. But so long as means of production are privately owned and the profit motive remains the engine at the heard of our economy, what we get instead is a permanent crisis of overproduction.

:::

Things that get pastiched through AI have already been sucked dry vampire-like. They are already ubiquitous and lifeless, you don't need to come to their defense. If something has enough cultural weight to be parodied or imitated, whether by AI, nerdy t-shirt sellers or fanartists, that usually means that this particular cultural phenomenon has escaped the category of "artist's work" and entered the domain of mass marketed meme or brand. I believe this to be equally true of fashion house logos that get bootlegged, marvel slop, and more beloved examples like the "classic ghibli style". My more personal and less marxist take on this is: pastiche of household "art styles" is fundamentally tacky whether it's done by an AI program or a "real human artist", and fandom is a disease.

:::

The AI market bubble is currently fueling the reexpansion of fossil fuel extraction and consumption in the western world, and that alone is a legitimate basis to oppose AI technologies on a general basis. However, as already said in the main body of this post, only the organized working class is poised to carry out this fight.

Annex: