SOME LESSONS TO LEARN FROM RIVEN

ALSO WHY I HATED BIOSHOCK INFINITE

···

//Beforehand: this "essay" kind of was initially written as a school assignment. Please excuse its very school-ish structure, even though I took liberties translating it. Excuse also my wonky english.

···

Riven, second opus of the Myst series, is amongst the games that were the most inspirational to me, if not the one most impactful. As my school asked for an essay on a subject of our choice, I decided to analyse the reasons this game fascinated me so much and to compare this with what the industry offers us today.

One of my main focus regards the way the industry aims to affirm the cultural legitimacy of videogames by applying cinematographic tropes, while Riven and the other games I studied explore different paths.

As such, this file only talks about games that imply an avatar (either clearly identified or not, see first-person games) under the player's control, wandering in an environment. That's what we could call "conventional usual games", and excludes most arcade & mobile games, not to mention games exploring new possibility spaces outside of usual conventions. Still, a majority of games fit these criteria.

I don't want to promote these games as an absolute model, since video games as a media are extremely varied and offer almost endless possibilities. My goal is to raise interesting points from games that are dear to me, that are relevant to their media and interesting to keep in mind.

One of my main focus regards the way the industry aims to affirm the cultural legitimacy of videogames by applying cinematographic tropes, while Riven and the other games I studied explore different paths.

As such, this file only talks about games that imply an avatar (either clearly identified or not, see first-person games) under the player's control, wandering in an environment. That's what we could call "conventional usual games", and excludes most arcade & mobile games, not to mention games exploring new possibility spaces outside of usual conventions. Still, a majority of games fit these criteria.

I don't want to promote these games as an absolute model, since video games as a media are extremely varied and offer almost endless possibilities. My goal is to raise interesting points from games that are dear to me, that are relevant to their media and interesting to keep in mind.

//EXPLORATION, EXPERIMENTATION & COMPREHENSION OF A SYSTEM

Riven is a point-and-click exploration/puzzle game, based on the same system as its predecessor Myst. However, most games based on enigmas and even Myst itself don't work as subtly as Riven.

·

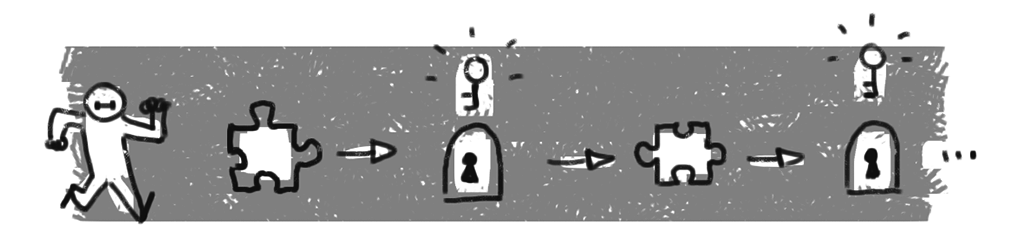

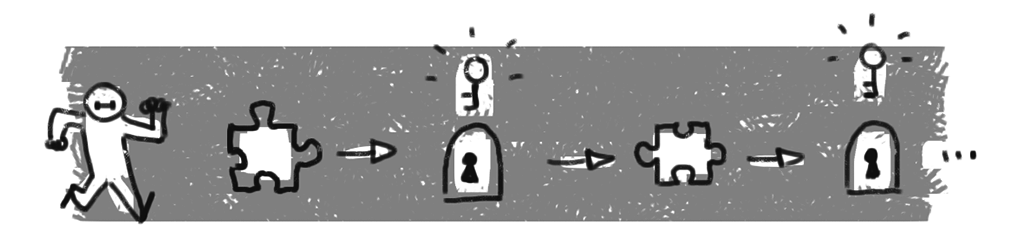

A mistake many puzzle games tend to tap into is the superficiality and linearity of all enigmas as an ensemble: in many puzzle games they act independently and arbitrarily block the player's progression. Each enigma (or set of a few similar enigmas) unlocks the door to the next section of the game, consisting itself of another set of enigmas and a door.

Exploration/puzzle games prove more interesting if they offer a coherent system to apprehend and an internal language to decipher, rather than a sequence of riddles relying on tricks.

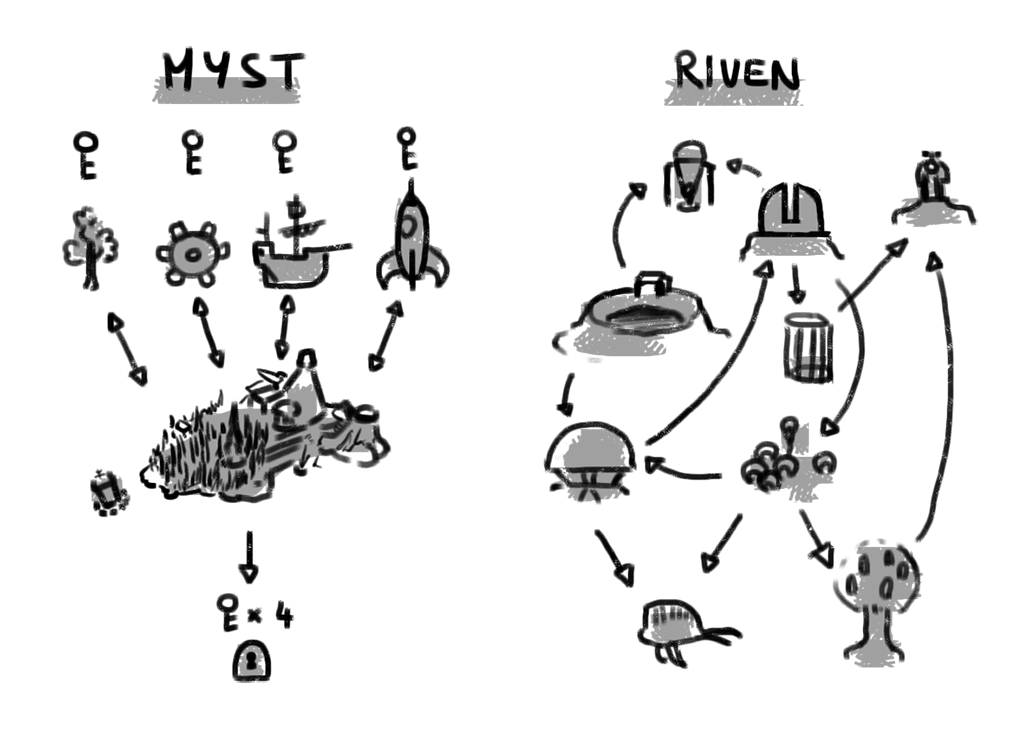

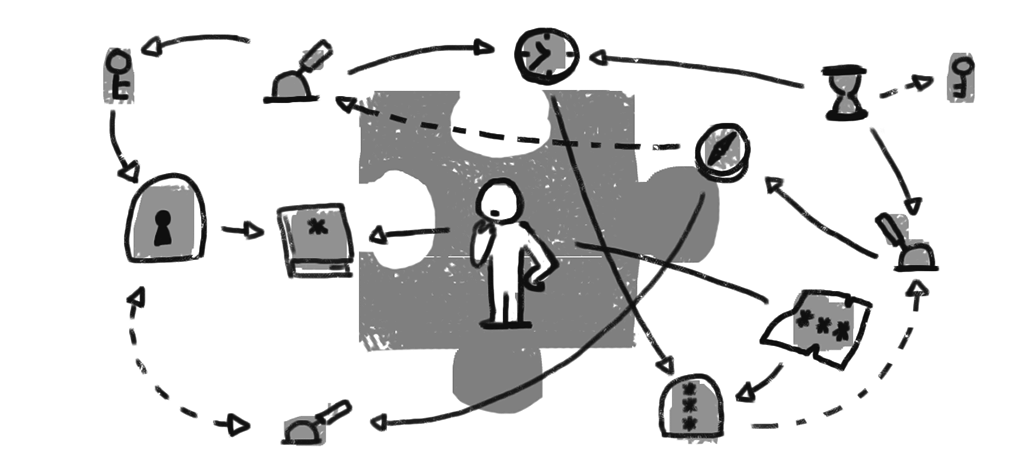

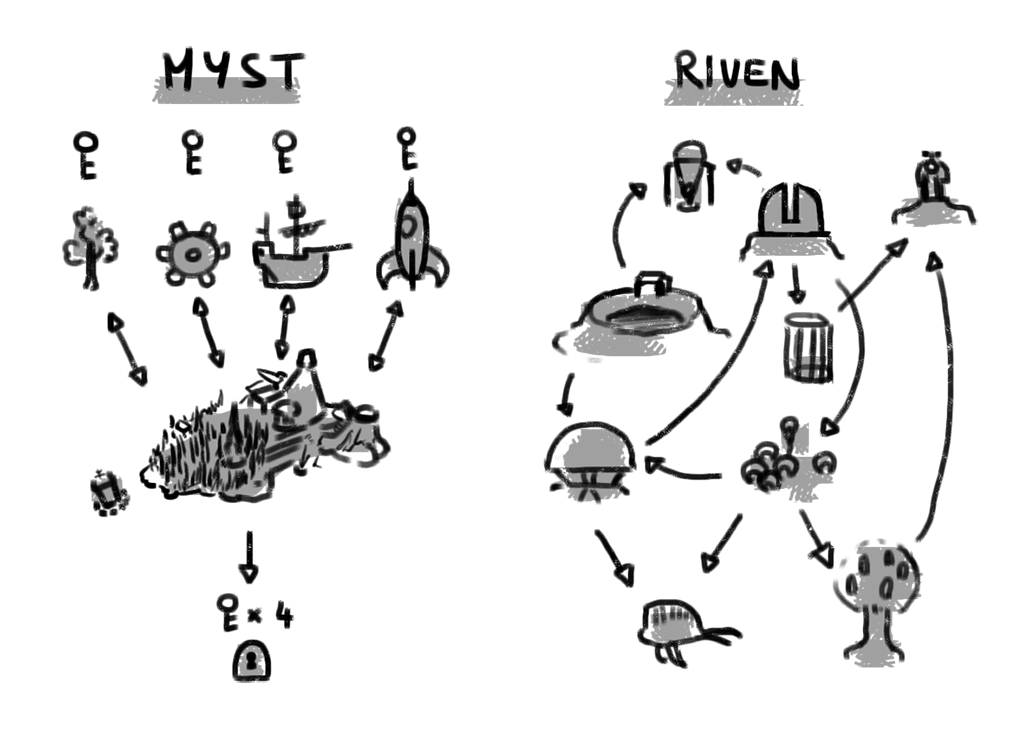

That's a sensible difference between Myst and its sequel Riven. In Myst, although the various puzzles are clever and not trivial, the general structure of the game is obvious. Every parallel age is an independent puzzle that must be solved to obtain a page, and collecting all pages unlocks the end of the game as a key would. On the other hand, Riven sets up a sole and coherent universe, in which all spaces of the game (five islands) are connected to one another: the game's structure is intricate, organic and seamless.

This issue is wide-spread and many are the games that, like Myst, let the structure of puzzles-and-doors totally apparent.

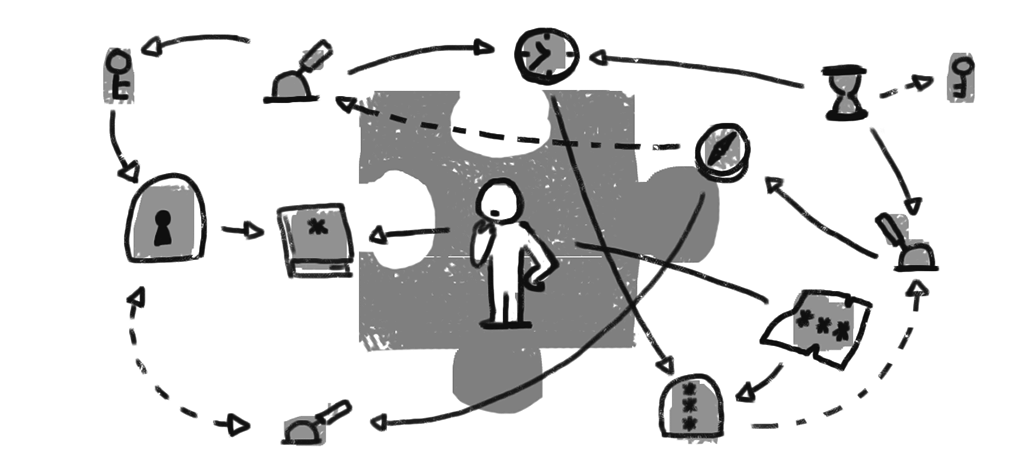

It all comes down to a necessity to offer an organic puzzle system rather than a linear sequence of enigmas: this implies that the whole game must be thought as a non-linear game, in every aspect, as a linear game would imply a forced order in the learning of all pieces of the general problem. For the player to have the opportunity to tackle the problem from whichever angle they see fitting, it is necessary to let them wander in an open playing space. The general puzzle then consists of recurrent symbols and motives that the player learns to understand and link together, little by little understanding the internal logic that ties everything together.

·

In Riven, the challenge doesn't rely on action nor in learning and then reproducing or applying schemes, but rather on curiosity and experimentation as a way to understand the rules of the environment. The player really has the opportunity to toy around with their environment as a playground, letting them face the challenge on whatever angle they choose, with little skill required if any at all. This is a comeback to the very basis of play and amusement, relying on the manipulation of items (concrete or abstract) as a mean to learn and understand how a system works, what the underlying logic is.

Moreover, by offering the player a challenge based on reflexion and comprehension rather than the brutal opposition with an antagonist, games can appeal to a broader audience than their usual while answering some recurrent - and valid - reproaches such as an excessive violence and a machist vision of violence as a conflict solver. It also prevents the player from focusing on enemies and interactive items (healthpacks or else) and thus developing some kind of x-ray vision that is frequent in action games, and particularly in shooters. The environment and its development can be totally overlooked by players focused on enemies and pickups. As a side note, this issue can also occur in games from other genres: platformers for instance often have identifiable interactive items such as springboards etc. that trigger the same analytic vision of the environment.

·

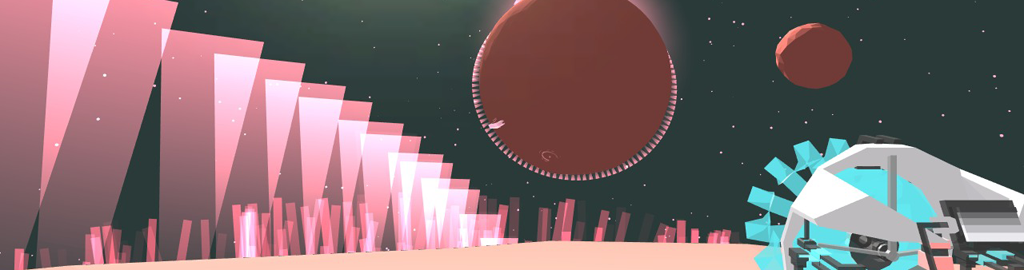

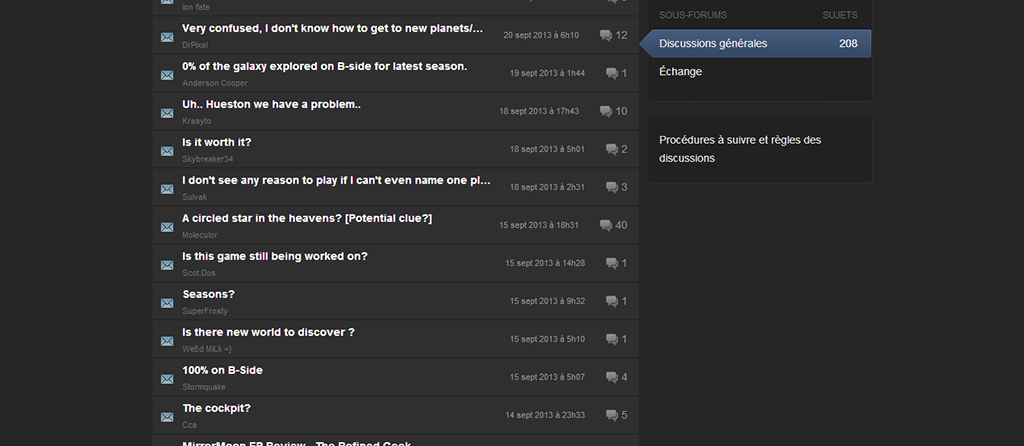

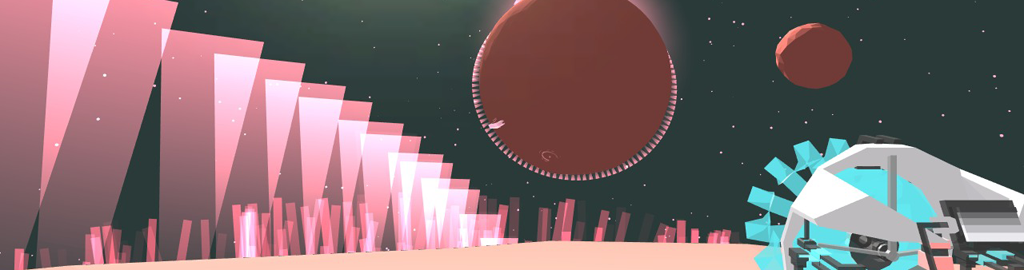

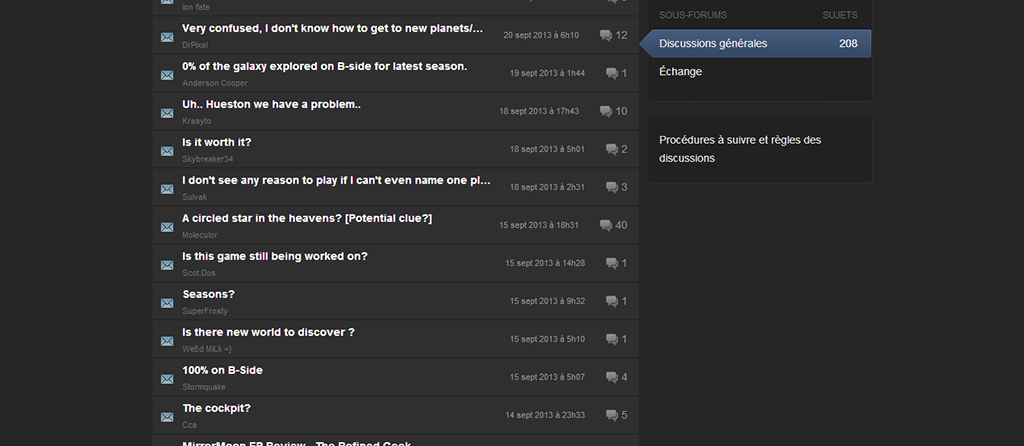

In a game based on exploration, it is critical to maintain the player's focus and avoid them getting lost (as in, unable to reconnect with the place they come from - temporary spatial confusion isn't an issue) or, more importantly, get stuck and give up. Mirror Moon EP by Santa Ragione (otherwise one of the best games ever play it ok bye) is problematic in that it doesn't give any indication to the player about how to progress through the game.

Many players ended up frustrated to not know where to go nor, much more importantly, whether there actually was anything more to find in the first place.

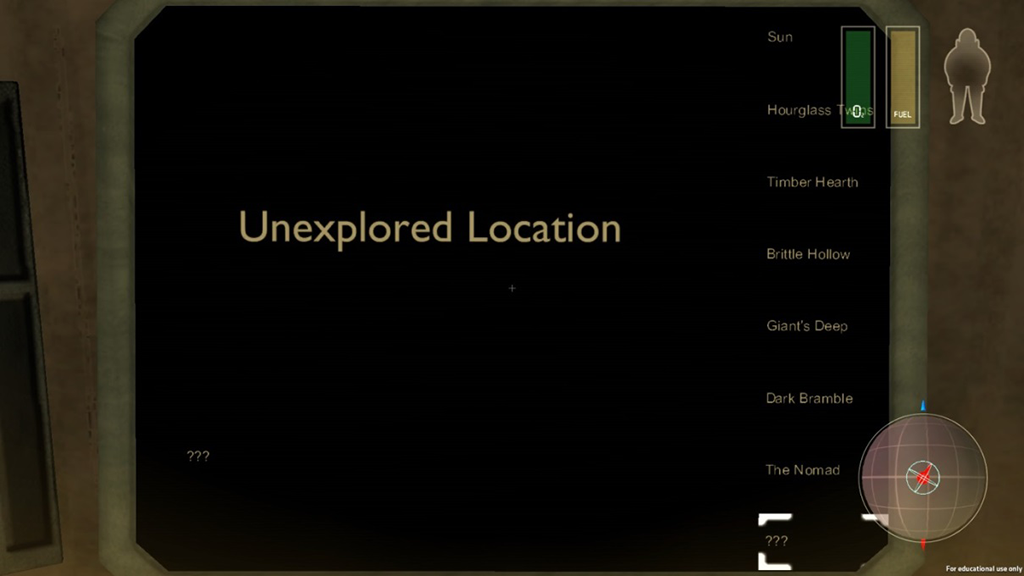

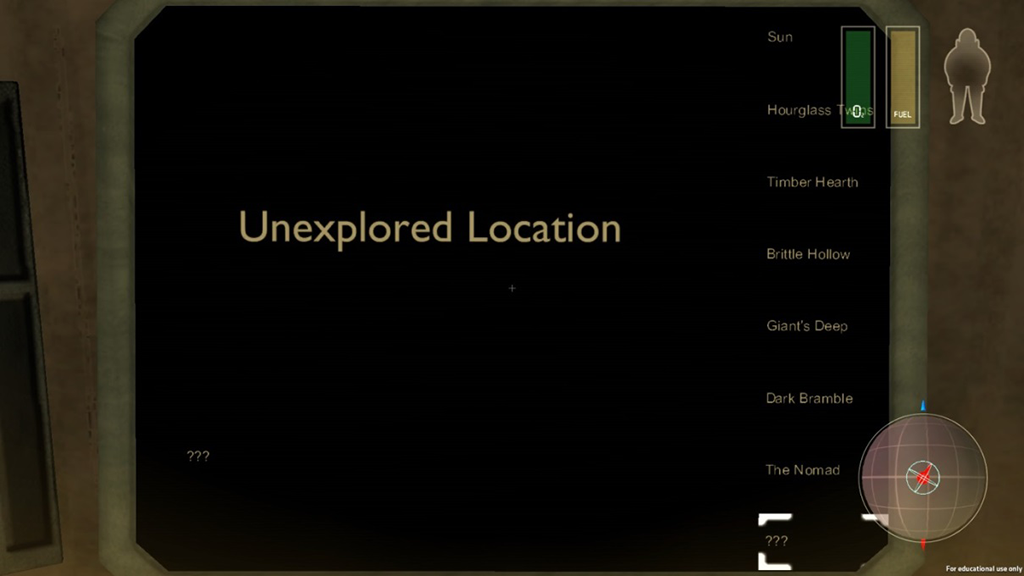

Then there's Outer Wilds, an in-development student game that solved this issue and maintains the player's focus even though they are offered a total exploration freedom. In the game, the player gets to be a space explorer wandering around the solar system of their home planet in their lil' spaceship, stepping down on various planets to find clues of what's going on.

At the beginning of the game, the player has access to a planet list, that ends up with a mysterious entry only named "????". This acts as a trigger for the player's curiosity, and thus the search for the mysterious planet will act as the main drive to their exploration. Visiting the planets, they discover clues that connect to one another, leaving the player with multiple directions. It is frequent to find on a planet a clue that allows progress on another one, and so the player can visit each planet multiple times, each time digging further in the successive layers of exploration available and discovering new elements that they totally overlooked at the first sight. Lastly, a particularity of the game is that a time anomaly resets the whole playground every 8 minutes: this imposes a time limit to the player, which means that they will never be able to explore a whole planet in just one loop, and prevents them to spend too much time at the same place and get bored.

The game provides the player with multiple clues that give the player multiple possible directions, while at the same time sending them regularly back to the beginning to incite them to explore a bit of everything, rather than focusing all their time on a planet before moving on.

There are other ways to avoid the issue of players getting stuck or lost. In Proteus for example, the path to the endgame is obvious, indicated by fireflies; but many secrets can be discovered during each season of the game and act as facultative rewards for explorers, rather than keys blocking the progression. An impatient player will therefore not be frustrated nor lost, but a player compelled by the game's mood can also fool around freely.

Riven is a point-and-click exploration/puzzle game, based on the same system as its predecessor Myst. However, most games based on enigmas and even Myst itself don't work as subtly as Riven.

·

A mistake many puzzle games tend to tap into is the superficiality and linearity of all enigmas as an ensemble: in many puzzle games they act independently and arbitrarily block the player's progression. Each enigma (or set of a few similar enigmas) unlocks the door to the next section of the game, consisting itself of another set of enigmas and a door.

Exploration/puzzle games prove more interesting if they offer a coherent system to apprehend and an internal language to decipher, rather than a sequence of riddles relying on tricks.

That's a sensible difference between Myst and its sequel Riven. In Myst, although the various puzzles are clever and not trivial, the general structure of the game is obvious. Every parallel age is an independent puzzle that must be solved to obtain a page, and collecting all pages unlocks the end of the game as a key would. On the other hand, Riven sets up a sole and coherent universe, in which all spaces of the game (five islands) are connected to one another: the game's structure is intricate, organic and seamless.

This issue is wide-spread and many are the games that, like Myst, let the structure of puzzles-and-doors totally apparent.

It all comes down to a necessity to offer an organic puzzle system rather than a linear sequence of enigmas: this implies that the whole game must be thought as a non-linear game, in every aspect, as a linear game would imply a forced order in the learning of all pieces of the general problem. For the player to have the opportunity to tackle the problem from whichever angle they see fitting, it is necessary to let them wander in an open playing space. The general puzzle then consists of recurrent symbols and motives that the player learns to understand and link together, little by little understanding the internal logic that ties everything together.

·

In Riven, the challenge doesn't rely on action nor in learning and then reproducing or applying schemes, but rather on curiosity and experimentation as a way to understand the rules of the environment. The player really has the opportunity to toy around with their environment as a playground, letting them face the challenge on whatever angle they choose, with little skill required if any at all. This is a comeback to the very basis of play and amusement, relying on the manipulation of items (concrete or abstract) as a mean to learn and understand how a system works, what the underlying logic is.

Moreover, by offering the player a challenge based on reflexion and comprehension rather than the brutal opposition with an antagonist, games can appeal to a broader audience than their usual while answering some recurrent - and valid - reproaches such as an excessive violence and a machist vision of violence as a conflict solver. It also prevents the player from focusing on enemies and interactive items (healthpacks or else) and thus developing some kind of x-ray vision that is frequent in action games, and particularly in shooters. The environment and its development can be totally overlooked by players focused on enemies and pickups. As a side note, this issue can also occur in games from other genres: platformers for instance often have identifiable interactive items such as springboards etc. that trigger the same analytic vision of the environment.

·

In a game based on exploration, it is critical to maintain the player's focus and avoid them getting lost (as in, unable to reconnect with the place they come from - temporary spatial confusion isn't an issue) or, more importantly, get stuck and give up. Mirror Moon EP by Santa Ragione (otherwise one of the best games ever play it ok bye) is problematic in that it doesn't give any indication to the player about how to progress through the game.

Many players ended up frustrated to not know where to go nor, much more importantly, whether there actually was anything more to find in the first place.

Then there's Outer Wilds, an in-development student game that solved this issue and maintains the player's focus even though they are offered a total exploration freedom. In the game, the player gets to be a space explorer wandering around the solar system of their home planet in their lil' spaceship, stepping down on various planets to find clues of what's going on.

At the beginning of the game, the player has access to a planet list, that ends up with a mysterious entry only named "????". This acts as a trigger for the player's curiosity, and thus the search for the mysterious planet will act as the main drive to their exploration. Visiting the planets, they discover clues that connect to one another, leaving the player with multiple directions. It is frequent to find on a planet a clue that allows progress on another one, and so the player can visit each planet multiple times, each time digging further in the successive layers of exploration available and discovering new elements that they totally overlooked at the first sight. Lastly, a particularity of the game is that a time anomaly resets the whole playground every 8 minutes: this imposes a time limit to the player, which means that they will never be able to explore a whole planet in just one loop, and prevents them to spend too much time at the same place and get bored.

The game provides the player with multiple clues that give the player multiple possible directions, while at the same time sending them regularly back to the beginning to incite them to explore a bit of everything, rather than focusing all their time on a planet before moving on.

There are other ways to avoid the issue of players getting stuck or lost. In Proteus for example, the path to the endgame is obvious, indicated by fireflies; but many secrets can be discovered during each season of the game and act as facultative rewards for explorers, rather than keys blocking the progression. An impatient player will therefore not be frustrated nor lost, but a player compelled by the game's mood can also fool around freely.

//ON COHERENCE

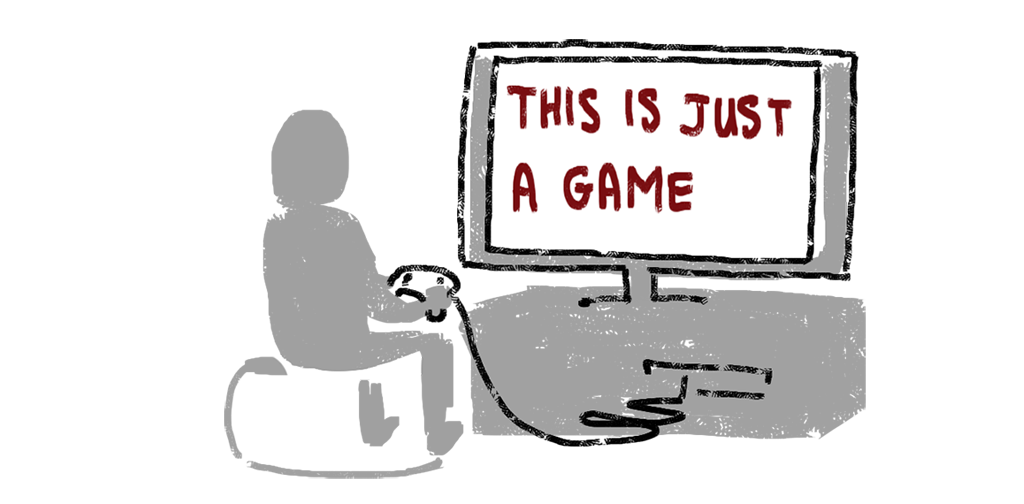

For the narration's and the universe's depths to be properly expressed by the game, the game needs to be coherent and credible to the player's eyes. It must behave according to an internal logic while the work of the developers has to be seamless and invisible. See the notion of suspension of disbelief: the player can ignore differences between the game and real life provided the game doesn't remind them of its nature by exposing its structure nor its underlying mechanics in an obvious fashion.

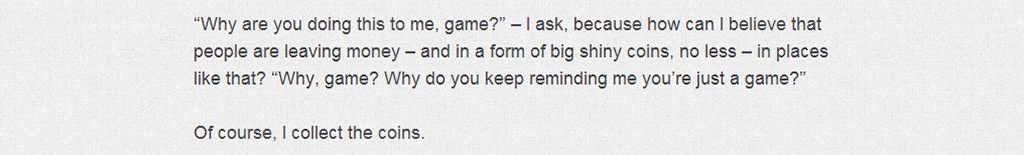

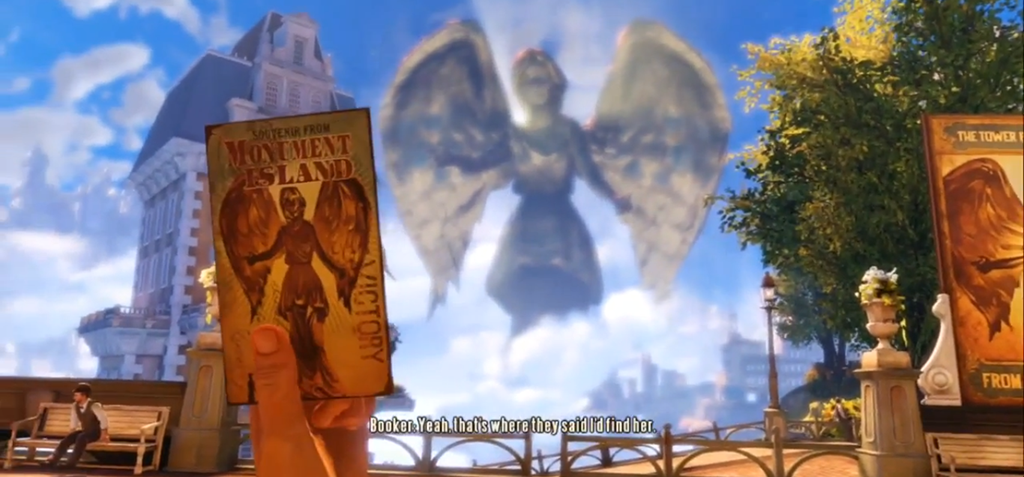

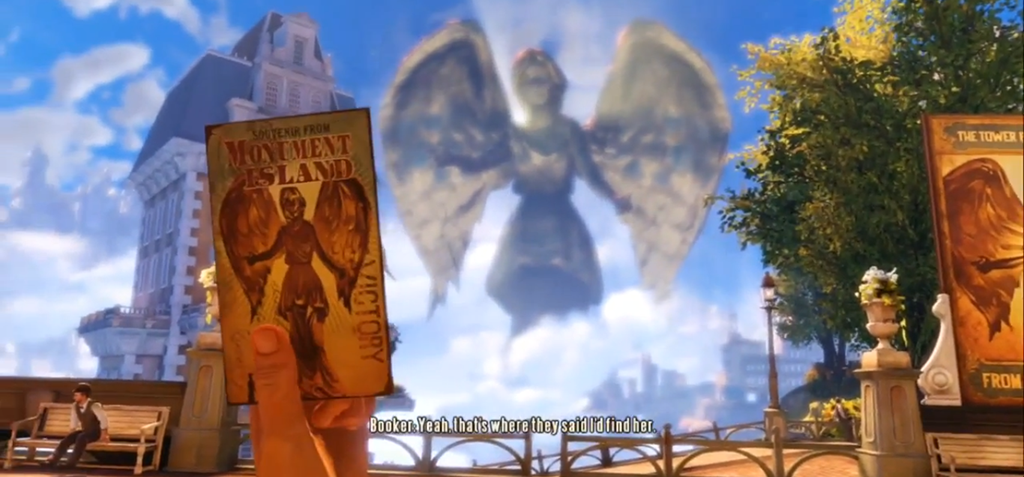

For instance, the game Bioshock Infinite rewards the player's exploration with coins that do not consist a critical gain, but merely tell them "hey thanks for getting to the end of this corridor well done, here have a coin so you know it's the end and there's nothing else to look for here". These elements are VERY usual in videogames, and the obsession some developers have to reward every single of the player's actions can seriously weaken their immersion : it can be more interesting to not offer the player any reward at all, or a discrete visual/audible/sensorial/narrative one, when they explore some parts of the levels. So we feel like we actually wander in a world that lives for itself and doesn't care, rather than a playground put in place for the pleasure of us-the-players, with the developers winking at us from behind their factice scenery. For a more consistent essay on this point, see the article linked at the bottom of the page.

·

Immersion does not depend on simulation or realism, but on the coherence of the system and its rules. Credibility is important, not realism (same goes, by the way, for movies).

As far as the game lives by axioms that never break, the player will not feel pulled out of their immersion: the avatar in Riven never has to eat, to take a poopy nor to sleep, nor does time ever seem to pass at all, but who cares? However, if one of these rules was to be broken at one point of the game, e.g. for scenario purposes, the incoherence could weaken the game's consistency (key word here). For instance, the Tomb Raider 2013 reboot uses Lara's hunger as the motivation for the deer-hunt sequence in which the player learns to hunt and use the bow. The issue is that Lara is never hungry ever again in the whole game, so it feels a bit out of touch and makes the actual purpose of the hunting session (resource collection and bow manipulation) very obvious.

On a side note, in puzzle/exploration game, it is often necessary for the player to write down notes on some elements - in Riven or Hiversaires it's actually pretty much impossible to make it to the end otherwise. But, even though it implies for the player to look away from the screen a bit, it isn't generally an issue for the player's immersion: as it doesn't imply a shift in the game's rhythm nor in its mood, it doesn't break the flow of the experience (I'll come back to this).

·

The absence of realistic non-playable-characters also let the players free to behave as they wish without incoherence. The illogical behaviour of NPCs, albeit sometimes very entertaining, will pretty much always pull the player out of their immersion.

There's no entity in either Riven or Outer Wilds that has the same status as the player's avatar. Therefore there's no risk for an illogical reaction from other characters, nor is there anyone to judge of the player's actions and they are left free to experiment. That last point is very dear to me : although it's less sensible than the one about illogical behaviours, it is tremendously important when the core of the experience relies on experimentation and therefore failure as a mean to learn (re: school is awful at teaching). For instance, the constant reactions of NPCs in the Assassin's Creed game, particularly when the avatar climbs structures, can make the player feel uneasy, unwanted, or simply annoyed; and generally send a negative message while climbing is supposed to be the most encouraged interaction throughout the game.

Still, it is possible to have non playable characters in the game without breaking the player's immersion, but it is necessary to justify by a specific status the fact that they don't have the same capabilities the player's avatar has. It can be an axiom itself : in FJORDS, the characters only express themselves through a single elementary sentence repeated over and over, making it clear that they can't communicate properly with the player.

·

In Riven and in Outer Wilds, the actions of the avatar within the game's world are similar to the actions of the player towards the game : in both cases it's about understanding a system and solving it. The immersion and the identification of the player are thus encouraged : this is what I already suggested about writing notes not pulling the player out of their flow. This action is exactly what the player would do if they really were the avatar they pretend to be, and the distinction between the game's world and the real world is not blatant.

Moreover, the gameplay of both games is consistent, without any exotic or intrusive gameplay sequences. There's no rupture in the continuum, which allows for a stronger coherence, while games using brutal rhythm variations (quick time events, games featuring many distinct phases with different gameplays...) might startle the player.

Although, in Riven, the player's action is contextual (a click can open a door, trigger a mechanism, take a notebook, trigger a movement...); the action's gameplay is always the same. The player interacts with clicks and there's no change in the rhythm nor in the challenge type (as in, the player will never be asked to click quickly or use actual physical skill). Similarly, in Outer Wilds, both gameplays (moving with the spaceship or outside of it) are tied together as the point of view never changes and the controls stay similar, so there's no rupture.

As another side note, I think the point-and-click controls, albeit overlooked today in favour of WASD movement, are particularly relevant to this type of games. They shift the focus from movement to observation and reflexion, and avoid falling in the "good puzzle, bad platformer" trope. If a game has platform-like movements (2D or 3D), the movement must be a consistent part of the game's experience. The focus in Riven is solely on the reflexion part, so aside of the technical constraint, I also think it is relevant as an actual choice. On the other hand, Outer Wilds makes it entertaining to move around in the solar system, hopping in and out of the spaceship depending on the distance to travel, and using the jetpack with care as gravity on these little planets can be tricky; thus justifying the platform part of the game and making movement part of the experience, and not just a boring obstacle.

For the narration's and the universe's depths to be properly expressed by the game, the game needs to be coherent and credible to the player's eyes. It must behave according to an internal logic while the work of the developers has to be seamless and invisible. See the notion of suspension of disbelief: the player can ignore differences between the game and real life provided the game doesn't remind them of its nature by exposing its structure nor its underlying mechanics in an obvious fashion.

For instance, the game Bioshock Infinite rewards the player's exploration with coins that do not consist a critical gain, but merely tell them "hey thanks for getting to the end of this corridor well done, here have a coin so you know it's the end and there's nothing else to look for here". These elements are VERY usual in videogames, and the obsession some developers have to reward every single of the player's actions can seriously weaken their immersion : it can be more interesting to not offer the player any reward at all, or a discrete visual/audible/sensorial/narrative one, when they explore some parts of the levels. So we feel like we actually wander in a world that lives for itself and doesn't care, rather than a playground put in place for the pleasure of us-the-players, with the developers winking at us from behind their factice scenery. For a more consistent essay on this point, see the article linked at the bottom of the page.

·

Immersion does not depend on simulation or realism, but on the coherence of the system and its rules. Credibility is important, not realism (same goes, by the way, for movies).

As far as the game lives by axioms that never break, the player will not feel pulled out of their immersion: the avatar in Riven never has to eat, to take a poopy nor to sleep, nor does time ever seem to pass at all, but who cares? However, if one of these rules was to be broken at one point of the game, e.g. for scenario purposes, the incoherence could weaken the game's consistency (key word here). For instance, the Tomb Raider 2013 reboot uses Lara's hunger as the motivation for the deer-hunt sequence in which the player learns to hunt and use the bow. The issue is that Lara is never hungry ever again in the whole game, so it feels a bit out of touch and makes the actual purpose of the hunting session (resource collection and bow manipulation) very obvious.

On a side note, in puzzle/exploration game, it is often necessary for the player to write down notes on some elements - in Riven or Hiversaires it's actually pretty much impossible to make it to the end otherwise. But, even though it implies for the player to look away from the screen a bit, it isn't generally an issue for the player's immersion: as it doesn't imply a shift in the game's rhythm nor in its mood, it doesn't break the flow of the experience (I'll come back to this).

·

The absence of realistic non-playable-characters also let the players free to behave as they wish without incoherence. The illogical behaviour of NPCs, albeit sometimes very entertaining, will pretty much always pull the player out of their immersion.

There's no entity in either Riven or Outer Wilds that has the same status as the player's avatar. Therefore there's no risk for an illogical reaction from other characters, nor is there anyone to judge of the player's actions and they are left free to experiment. That last point is very dear to me : although it's less sensible than the one about illogical behaviours, it is tremendously important when the core of the experience relies on experimentation and therefore failure as a mean to learn (re: school is awful at teaching). For instance, the constant reactions of NPCs in the Assassin's Creed game, particularly when the avatar climbs structures, can make the player feel uneasy, unwanted, or simply annoyed; and generally send a negative message while climbing is supposed to be the most encouraged interaction throughout the game.

Still, it is possible to have non playable characters in the game without breaking the player's immersion, but it is necessary to justify by a specific status the fact that they don't have the same capabilities the player's avatar has. It can be an axiom itself : in FJORDS, the characters only express themselves through a single elementary sentence repeated over and over, making it clear that they can't communicate properly with the player.

·

In Riven and in Outer Wilds, the actions of the avatar within the game's world are similar to the actions of the player towards the game : in both cases it's about understanding a system and solving it. The immersion and the identification of the player are thus encouraged : this is what I already suggested about writing notes not pulling the player out of their flow. This action is exactly what the player would do if they really were the avatar they pretend to be, and the distinction between the game's world and the real world is not blatant.

Moreover, the gameplay of both games is consistent, without any exotic or intrusive gameplay sequences. There's no rupture in the continuum, which allows for a stronger coherence, while games using brutal rhythm variations (quick time events, games featuring many distinct phases with different gameplays...) might startle the player.

Although, in Riven, the player's action is contextual (a click can open a door, trigger a mechanism, take a notebook, trigger a movement...); the action's gameplay is always the same. The player interacts with clicks and there's no change in the rhythm nor in the challenge type (as in, the player will never be asked to click quickly or use actual physical skill). Similarly, in Outer Wilds, both gameplays (moving with the spaceship or outside of it) are tied together as the point of view never changes and the controls stay similar, so there's no rupture.

As another side note, I think the point-and-click controls, albeit overlooked today in favour of WASD movement, are particularly relevant to this type of games. They shift the focus from movement to observation and reflexion, and avoid falling in the "good puzzle, bad platformer" trope. If a game has platform-like movements (2D or 3D), the movement must be a consistent part of the game's experience. The focus in Riven is solely on the reflexion part, so aside of the technical constraint, I also think it is relevant as an actual choice. On the other hand, Outer Wilds makes it entertaining to move around in the solar system, hopping in and out of the spaceship depending on the distance to travel, and using the jetpack with care as gravity on these little planets can be tricky; thus justifying the platform part of the game and making movement part of the experience, and not just a boring obstacle.

//A NARRATION RELEVANT TO THE MEDIA aka what my teachers call narrative emergence

A sensible drive in the current game industry is to try and give cultural legitimacy to videogames by applying cinematographic tropes to them in terms of narration.

The result is mitigated, as the polemics around David Cage's productions and the uneven reception of Bioshock Infinite show : for instance, Bioshock Infinite's success is in big part due to its plot twists that occurs in the last minutes of the game, without offering any consistent interaction; and the irrelevancy of the game's gameplay in regards to its story resonates with the notion of ludonarrative dissonance that has been big in the conversations these last years. Dissonance has also been the main reproach aimed at the Tomb Raider reboot where a supposed "survivor striving to save her own life" ends up committing a murderous rampage in gameplay phases, killing everything in sight.

·

This type of narration, breed from cinema and literature, focuses on characters, in particular on the protagonist: the story follows their evolution and maturation. So there's always this main character who is imperfect and will follow a Campbell-style hero's journey to learn, become a hero and further prove their tru legitimacy. This character-focused storyline implies that the character have a strong, yet imperfect personality, as they must get better as the story goes: at the beginning of their initiatory journey, the hero often piles up issues such as arrogance, naiveté, immaturity, stupitidy, etc. (or even sometimes some kind of super-combo of all these, see Dante from the last Devil May Cry).

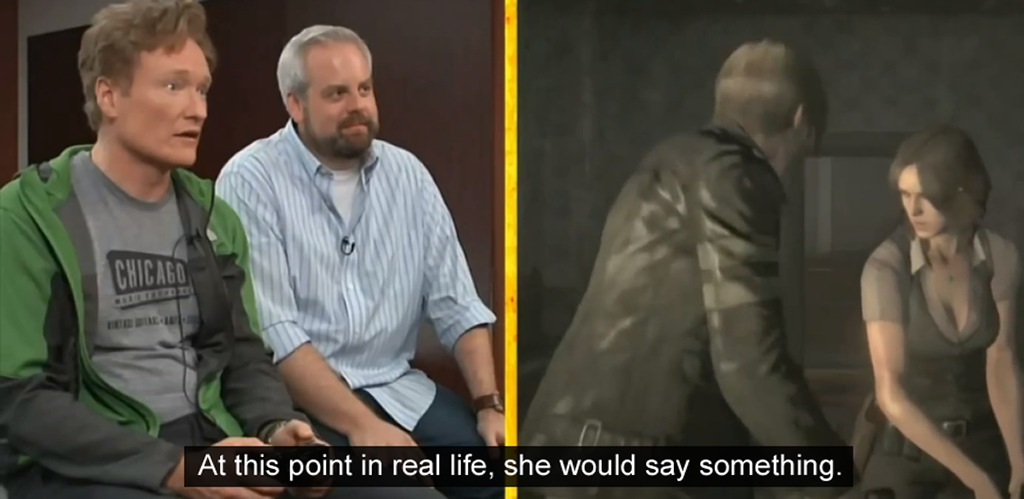

In the games I talked about before, the protagonist is also the player's vessel, therefore it becomes difficult to properly tie narration with immersion with such a storyline. First thing is, the protagonist's personality can be a huge hindrance for the player's identification with the avatar : Altaïr, in Assassin's Creed 1, is shown arrogant and violent right at the beginning of the game ; while Booker in Bioshock Infinite is nothing more than a brutal dumbass who also happens to talk aloud to himself. It's often uncomfortable and frustrating for a player to be forced into a stupid and annoying character's shoes, and that gets worse when said character constantly express themselves as a mean to further develop their personality, reminding the player of their existence in the process. See the way Booker's face gets reflected by mirrors and windows multiple times at the beginning of Bioshock Infinite, or the (so fucking annoying) way he talks to himself and grunts all the time before Elizabeth shows up to carry the conversation.

Second point: the uncanny mix of control and non-control the player's got on their character doesn't really go well. During gameplay phases, the player is in control of the avatar and imposes a certain rhythm and way of playing on them, a certain state of mind; but during scripted event the character can suddenly act in a drastically different manner. These moments can prove really hurtful for the player's immersion, suddenly taking away their control on a character they thought they finally were identifying with, and causing them to act in an opposite direction. Looking at the same examples, we can think of the end of Assassins's Creed 1 introduction sequence where, rather than approaching his opponents stealthily and taking them down one after another, Altaïr decides to call them from the other side of the room and brag about as he walks towards them, eventually causing the whole mission to fail; or there's this key episode of Bioshock Infinite where [SPOILERS AHEAD], as the player finally meets their main antagonist Comstock and hopes to obtain some answers, Booker takes control during a cutscene and instead decides that obliterating Comstock's skull on a marble vask without a word is definitely the most reasonable thing to do right now yeah sure good job. [END OF SPOILERS] These moments interrupt the player's flow and create at best suprise, at worst a frank frustration; and build antipathy towards the character that they are forced to embody.

·

The character-driven storyline development is built from the succession of key-events through time, and as such imposes a linear game. It creates a very restrictive space for the game to happen, with precise events and times at which stuff must happens, and thus force developers to restrain the player as much as they can.

·

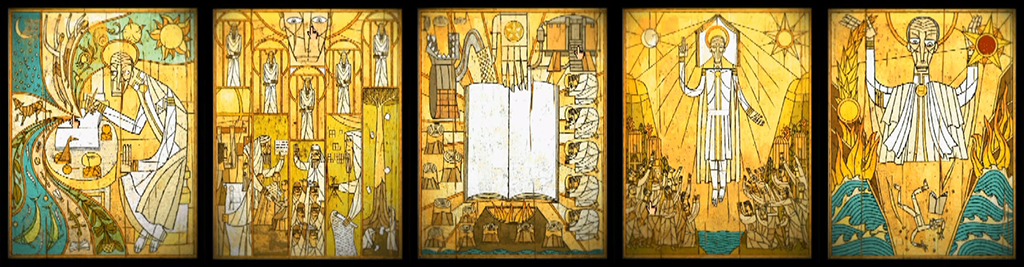

Contrary to these last games, the ones that I consider good examples tell their story though space rather than time, and use narrative emergence to develop the universe's story rather than the avatar's.

The term narrative emergence doesn't seem to have an official definition, or at least I didn't find anything on the matter myself, so for this file I am using this personal definition: I call "narrative emergence" the use of the game's environment as the primary mean to convey narrative elements to the player - Environmental Storytelling is another similar term, see the article linked at the bottom of the page. In the case of Riven, every element the player comes across during their playthrough allows them to discover and understand the game's universe, without it being explicitly introduced: thus they'll gradually discover [SPOILERS AHEAD] that the islands' inhabitants worship a divine figure, then that a whole chunk of the islands is actually inaccessible to them and occupied by said divine figure, who's thus revealed to be a human in possession of a superior technology. The player also find many elements allowing them to understand the culture of Riven's inhabitants, their numerical system, and other elements allowing them to progress through the game while its story unfolds.

[END OF SPOILERS]

Such a design allows players of all types to better immerse in the game: the player's avatar is barely defined at all and mute, because they are not an important part of the game's plot and often appear in the game as outsiders - which is precisely the status of the player when they first launch the game, and thus further connects the player to their avatar. The outsider status also justifies the weird posture of the avatar in regards to non-playable characters.

This, however, does not prohibit developers to clearly identify the character nor to develop their backstory. The critical point is that this story has to stay secondary and anecdotic compared to the universe's story. In Bioshock 2, the player impersonates a Big Daddy: none can tell what they look like under their apparatus but, in a secondary conversation, we learn that he used to be a diver who accidentally ended up in Rapture where he was brainwashed and made into a Big Daddy. This backstory doesn't impede on the player's immersion since, even though the player has to put themselves in the character's shoes, it doesn't give any further precision on the character's temper and leave the player free to choose their attitude and behaviour, to actually project themselves in the game through their avatar.

Some games actually play on that weird stance of the avatar, the most famous example probably being Gordon Freeman who's muteness is laughingly observed by his companions, or the game Zork: Grand Inquisitor in which the player is ironically called "Ageless, Faceless, Gender-Neutral, Culturally Ambiguous Adventure Person" by their acolyte (for I have not played any other game from the Zork series, I can't say if this stance is consistent in the whole series or specific to this episode). Anyway Gordon Freeman's example is especially remarkable as, even though he doesn't actually have any personality at all, he still eventually became a pop-culture reference.

·

Rather than relying on time as the mean to tell the story, narrative emergence shifts the focus to space (both visual and audio). Narration is carried by what the player constantly sees and hears (ie. the environment) rather than relying on cutscenes or one-shot punctual scripted events, as it is often the case in recent AAA productions. Moreover, by using the environment to convey the story, narrative emergence rewards players' curiosity and encourage exploration.

This focus on environment is therefore particularly relevant in games banking on exploration and observation in their gameplay, rather than the opposition against antagonists in an action-oriented gameplay (see part. 1).

Narrative emergence makes a stronger impression on players and grants the game a greater emotional impact since it encourages players to be actually attentive about the details of the environment they visit, to notice links between the elements they find out and actually engage in a reflexion about the game's universe.

A sensible drive in the current game industry is to try and give cultural legitimacy to videogames by applying cinematographic tropes to them in terms of narration.

The result is mitigated, as the polemics around David Cage's productions and the uneven reception of Bioshock Infinite show : for instance, Bioshock Infinite's success is in big part due to its plot twists that occurs in the last minutes of the game, without offering any consistent interaction; and the irrelevancy of the game's gameplay in regards to its story resonates with the notion of ludonarrative dissonance that has been big in the conversations these last years. Dissonance has also been the main reproach aimed at the Tomb Raider reboot where a supposed "survivor striving to save her own life" ends up committing a murderous rampage in gameplay phases, killing everything in sight.

·

This type of narration, breed from cinema and literature, focuses on characters, in particular on the protagonist: the story follows their evolution and maturation. So there's always this main character who is imperfect and will follow a Campbell-style hero's journey to learn, become a hero and further prove their tru legitimacy. This character-focused storyline implies that the character have a strong, yet imperfect personality, as they must get better as the story goes: at the beginning of their initiatory journey, the hero often piles up issues such as arrogance, naiveté, immaturity, stupitidy, etc. (or even sometimes some kind of super-combo of all these, see Dante from the last Devil May Cry).

In the games I talked about before, the protagonist is also the player's vessel, therefore it becomes difficult to properly tie narration with immersion with such a storyline. First thing is, the protagonist's personality can be a huge hindrance for the player's identification with the avatar : Altaïr, in Assassin's Creed 1, is shown arrogant and violent right at the beginning of the game ; while Booker in Bioshock Infinite is nothing more than a brutal dumbass who also happens to talk aloud to himself. It's often uncomfortable and frustrating for a player to be forced into a stupid and annoying character's shoes, and that gets worse when said character constantly express themselves as a mean to further develop their personality, reminding the player of their existence in the process. See the way Booker's face gets reflected by mirrors and windows multiple times at the beginning of Bioshock Infinite, or the (so fucking annoying) way he talks to himself and grunts all the time before Elizabeth shows up to carry the conversation.

Second point: the uncanny mix of control and non-control the player's got on their character doesn't really go well. During gameplay phases, the player is in control of the avatar and imposes a certain rhythm and way of playing on them, a certain state of mind; but during scripted event the character can suddenly act in a drastically different manner. These moments can prove really hurtful for the player's immersion, suddenly taking away their control on a character they thought they finally were identifying with, and causing them to act in an opposite direction. Looking at the same examples, we can think of the end of Assassins's Creed 1 introduction sequence where, rather than approaching his opponents stealthily and taking them down one after another, Altaïr decides to call them from the other side of the room and brag about as he walks towards them, eventually causing the whole mission to fail; or there's this key episode of Bioshock Infinite where [SPOILERS AHEAD], as the player finally meets their main antagonist Comstock and hopes to obtain some answers, Booker takes control during a cutscene and instead decides that obliterating Comstock's skull on a marble vask without a word is definitely the most reasonable thing to do right now yeah sure good job. [END OF SPOILERS] These moments interrupt the player's flow and create at best suprise, at worst a frank frustration; and build antipathy towards the character that they are forced to embody.

·

The character-driven storyline development is built from the succession of key-events through time, and as such imposes a linear game. It creates a very restrictive space for the game to happen, with precise events and times at which stuff must happens, and thus force developers to restrain the player as much as they can.

·

Contrary to these last games, the ones that I consider good examples tell their story though space rather than time, and use narrative emergence to develop the universe's story rather than the avatar's.

The term narrative emergence doesn't seem to have an official definition, or at least I didn't find anything on the matter myself, so for this file I am using this personal definition: I call "narrative emergence" the use of the game's environment as the primary mean to convey narrative elements to the player - Environmental Storytelling is another similar term, see the article linked at the bottom of the page. In the case of Riven, every element the player comes across during their playthrough allows them to discover and understand the game's universe, without it being explicitly introduced: thus they'll gradually discover [SPOILERS AHEAD] that the islands' inhabitants worship a divine figure, then that a whole chunk of the islands is actually inaccessible to them and occupied by said divine figure, who's thus revealed to be a human in possession of a superior technology. The player also find many elements allowing them to understand the culture of Riven's inhabitants, their numerical system, and other elements allowing them to progress through the game while its story unfolds.

[END OF SPOILERS]

Such a design allows players of all types to better immerse in the game: the player's avatar is barely defined at all and mute, because they are not an important part of the game's plot and often appear in the game as outsiders - which is precisely the status of the player when they first launch the game, and thus further connects the player to their avatar. The outsider status also justifies the weird posture of the avatar in regards to non-playable characters.

This, however, does not prohibit developers to clearly identify the character nor to develop their backstory. The critical point is that this story has to stay secondary and anecdotic compared to the universe's story. In Bioshock 2, the player impersonates a Big Daddy: none can tell what they look like under their apparatus but, in a secondary conversation, we learn that he used to be a diver who accidentally ended up in Rapture where he was brainwashed and made into a Big Daddy. This backstory doesn't impede on the player's immersion since, even though the player has to put themselves in the character's shoes, it doesn't give any further precision on the character's temper and leave the player free to choose their attitude and behaviour, to actually project themselves in the game through their avatar.

Some games actually play on that weird stance of the avatar, the most famous example probably being Gordon Freeman who's muteness is laughingly observed by his companions, or the game Zork: Grand Inquisitor in which the player is ironically called "Ageless, Faceless, Gender-Neutral, Culturally Ambiguous Adventure Person" by their acolyte (for I have not played any other game from the Zork series, I can't say if this stance is consistent in the whole series or specific to this episode). Anyway Gordon Freeman's example is especially remarkable as, even though he doesn't actually have any personality at all, he still eventually became a pop-culture reference.

·

Rather than relying on time as the mean to tell the story, narrative emergence shifts the focus to space (both visual and audio). Narration is carried by what the player constantly sees and hears (ie. the environment) rather than relying on cutscenes or one-shot punctual scripted events, as it is often the case in recent AAA productions. Moreover, by using the environment to convey the story, narrative emergence rewards players' curiosity and encourage exploration.

This focus on environment is therefore particularly relevant in games banking on exploration and observation in their gameplay, rather than the opposition against antagonists in an action-oriented gameplay (see part. 1).

Narrative emergence makes a stronger impression on players and grants the game a greater emotional impact since it encourages players to be actually attentive about the details of the environment they visit, to notice links between the elements they find out and actually engage in a reflexion about the game's universe.

I'm not so good at elegant conclusions, so let's get straight to the point: Riven's relevancy towards video games as a media relies, to my mind, on three points:

A gameplay focused on reflexion and exploration set up within an organic, language-like structure rather than a linear series of workshops;

A set of non-realistic, but coherent rules that tie the fiction together and make it consistent; while the player's avatar is an outsider;

A narration focused on the game's world rather than the avatar's story, set up through "narrative emergence" or whatever you wanna call it, that works in a symbiotic way with the gameplay and furthers bounds the player and their avatar.

Traditional character-driven narrative models, as inherited from older medias (notably literature and cinema), do not prove fitting to videogames - at least not the conventional models of videogames, there's still a lot of space to explore with interactive medias. Ditching these narrative codes allows for a better focus on interactivity and leaves the player free to unveil the environment following their own impulse, rather than being forced into the developer's plan. The conventionnal storytelling model, focusing on the main character's arc, puts the creator in the position of a taleteller addressing a passive audience; while in videogames the creator builds a universe, that the players will then actively explore like archaeologists, looking for clues to help them understand the untold. I believe it is important to keep this in mind as we reflect on storytelling in games, thinking of it in terms of universe development and clues to unveil in a given space; instead of a character's evolution through time.

·

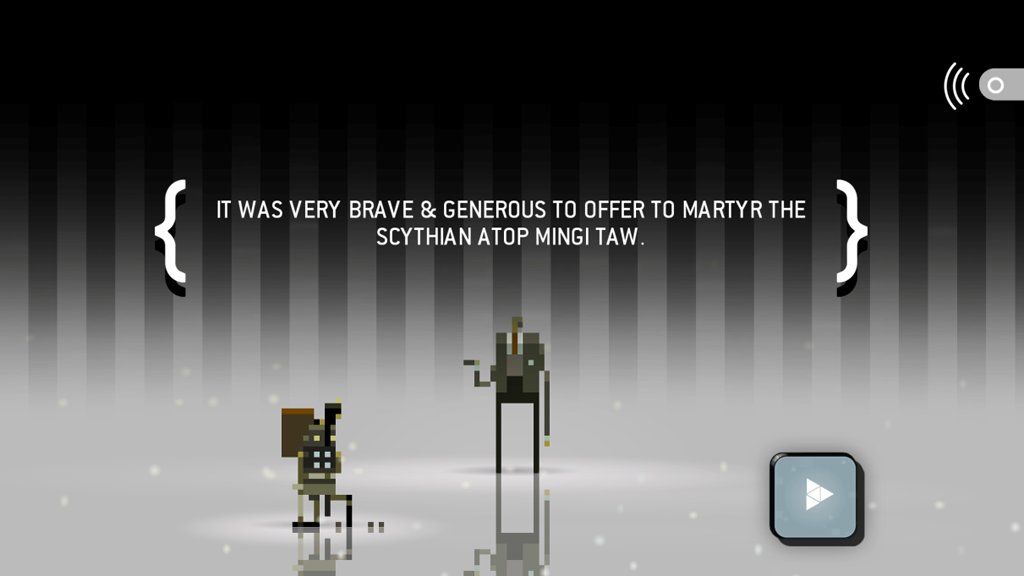

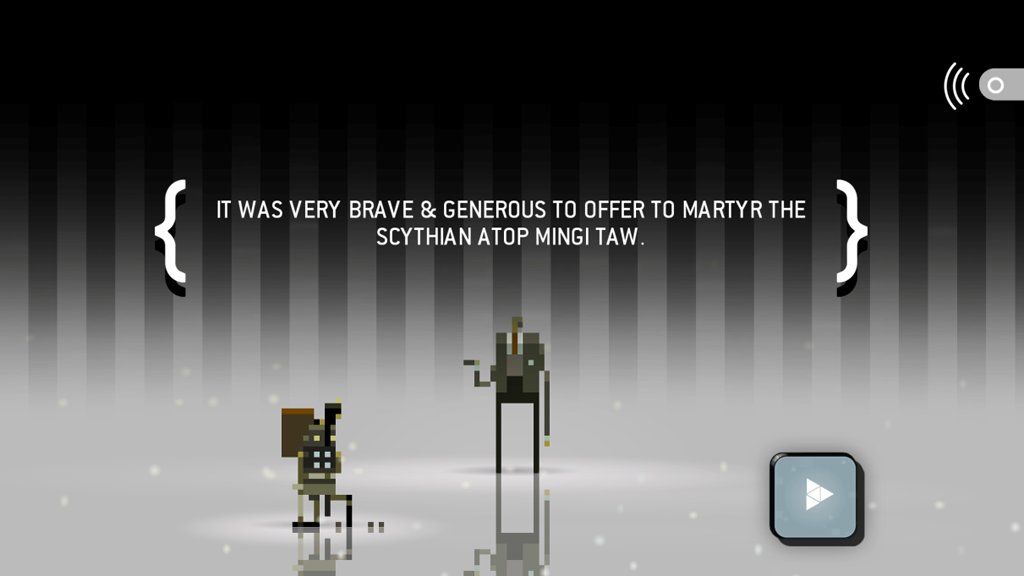

And then there are games that actually play with that weird bound between the player and their avatar on a meta level. I already mentioned Zork: Grand Inquisitor, but many recent games pushed this idea further, as OFF or Sword and Sworcery: EP did, by directly talking to the player and introducing their avatar as a separate entity, sometimes insisting on the somewhat unhealthy control the player have over their doll.

This actually reverses the situation. Where conventional games invite players to escape 'real life' in a fantasy world, these games choose to sneak into the player's reality, bringing some fancy to our daily lives.

This actually reverses the situation. Where conventional games invite players to escape 'real life' in a fantasy world, these games choose to sneak into the player's reality, bringing some fancy to our daily lives.

A gameplay focused on reflexion and exploration set up within an organic, language-like structure rather than a linear series of workshops;

A set of non-realistic, but coherent rules that tie the fiction together and make it consistent; while the player's avatar is an outsider;

A narration focused on the game's world rather than the avatar's story, set up through "narrative emergence" or whatever you wanna call it, that works in a symbiotic way with the gameplay and furthers bounds the player and their avatar.

Traditional character-driven narrative models, as inherited from older medias (notably literature and cinema), do not prove fitting to videogames - at least not the conventional models of videogames, there's still a lot of space to explore with interactive medias. Ditching these narrative codes allows for a better focus on interactivity and leaves the player free to unveil the environment following their own impulse, rather than being forced into the developer's plan. The conventionnal storytelling model, focusing on the main character's arc, puts the creator in the position of a taleteller addressing a passive audience; while in videogames the creator builds a universe, that the players will then actively explore like archaeologists, looking for clues to help them understand the untold. I believe it is important to keep this in mind as we reflect on storytelling in games, thinking of it in terms of universe development and clues to unveil in a given space; instead of a character's evolution through time.

·

And then there are games that actually play with that weird bound between the player and their avatar on a meta level. I already mentioned Zork: Grand Inquisitor, but many recent games pushed this idea further, as OFF or Sword and Sworcery: EP did, by directly talking to the player and introducing their avatar as a separate entity, sometimes insisting on the somewhat unhealthy control the player have over their doll.

This actually reverses the situation. Where conventional games invite players to escape 'real life' in a fantasy world, these games choose to sneak into the player's reality, bringing some fancy to our daily lives.

This actually reverses the situation. Where conventional games invite players to escape 'real life' in a fantasy world, these games choose to sneak into the player's reality, bringing some fancy to our daily lives.

···

FURTHER READING:

two insightful articles by Adrian Chmielarz

On invisible strings and worlds that live for themselves

On Bioshock Infinite's coins

Jethro Jongeneel on environmental storytelling

Environmental Storytelling in Games

two insightful articles by Adrian Chmielarz

On invisible strings and worlds that live for themselves

On Bioshock Infinite's coins

Jethro Jongeneel on environmental storytelling

Environmental Storytelling in Games